By: Hassanatu Kamara

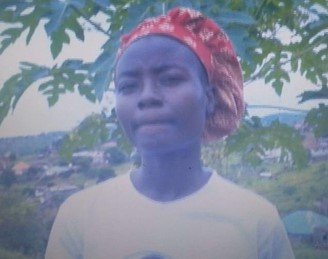

Every afternoon, ten-year-old Musu Fornah heads to the Danfo Quarry in Hastings,

Freetown to help her parents crush and pack stones. She said she dreams of excelling in school and spending time with friends, but Musu’s reality is shaped by long hours of heavy work, leaving her exhausted and struggling to keep up with her studies.

“Because my parents are poor and cannot afford other work, I have to work in the quarry. The heavy work makes me tired, which affects my studies and school performance,” she said.

Child labour remains a pressing issue in Sierra Leone, particularly within the stone mining industry, where children are often employed in hazardous conditions. Children are frequently seen working alongside their parents, relatives, and guardians at the

Danfo Quarry in Hastings. According to a report from the U.S. Department of State (2020), children participate in various mining-related activities. The report highlights that children in Sierra Leone are involved in hazardous tasks such as carrying sacks, loading gravel, and washing or sieving gravel—practices classified among the worst forms of child labor by the International Labour Organization (ILO). These practices violate international child labor standards.

In 2021, Sierra Leone made significant progress by ratifying several international conventions aimed at combating forced labor and human trafficking, thereby strengthening legal enforcement efforts. Data from 2020, published by the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL), highlighted the prevalence of child labor in the country. The report indicates that 35.1% of children aged 5-14 are engaged in work, while 78.2% attend school. Additionally, 32.2% of children aged 7-14 combine work and school activities, and the primary school completion rate stands at 83.2%. Within the industry sector, children commonly work in activities such as quarrying, stone crushing, and gravel shoveling, with prevalence rates ranging from 1.5% to 7%. Musu, a pupil at Ibza Innovation Academy, shares her daily routine: After attending school, she joined her parents at the quarry to assist with breaking and packing stones. Despite feeling tired and missing out on playtime, she said her family relies on her help to earn money for basic needs and school fees. She lamented that her family’s poverty limits her access to quality education and that quarry work hampers her academic performance.

Her mother, Aminata Sesay, who also has nine other children, said they all work in the quarry because they need the money to pay the children’ school fees. However, their earnings often aren’t enough.

“When the school sends my children home for unpaid fees, I have to plead with the teachers. If they refuse, my children cannot continue their education,” she said.

During these times, she said she pleads with teachers to allow her children to stay in school, but when they refuse, her children end up working with her. Aminata also revealed that after school, she sends her children to do laundry and joined them in crushing stones, often with little or no food to sustain them.

Ishmeal Turay, a young orphan who lost his parents several years ago, shared his story of struggle and perseverance.

“My parents passed away at an early age, leaving me alone with no savings to support myself. Since then, life has been challenging, which led me to drop out of school,” he said.

He described how life has been difficult, ultimately leading to his dropping out of school due to limited resources and lack of support to cover fees and expenses.

Nevertheless, he expressed gratitude to the workers at Danfo Quarry for giving him the opportunity to earn a living. Ishmeal now supports himself by collecting stones, which provide him with the means to meet his basic needs.

Despite the Child Rights Act of 2007, prohibiting children from engaging in hazardous work and setting the minimum employment age at 15, enforcement remains weak.

The Act permits some “light work” for younger children age 13, if it does not interfere with their education. However, many children continue to suffer from exploitation and adverse effects, highlighting gaps in policy implementation.

Zainab Sesay, a community teacher at the Living Word of Faith Nursery and Preparatory School in Hastings, described the harsh conditions faced by children involved in stone mining. She said many arrive at school in torn uniforms, hungry, and exhausted from their work in the quarry.

“Most of these children come from less privileged backgrounds where basic necessities are lacking, and educational resources are scarce. This situation hinders their development and that of their communities,” said Madam Sesay.

Despite efforts to educate parents about child labor laws, she said many are unable, or unwilling, to comply. Furthermore, she said that her school engages parents about laws against child labor. However, many respond that they cannot comply because they are single parents relying on their children’s work for survival. She said they argue that they cannot leave children at home while they work, as the income from quarrying is vital for their families.

Tamba Sorie, the District Supervisor for UNICEF’s project at Defence for Children International Sierra Leone, highlighted the alarming prevalence of child labor in communities and how hazardous work like quarrying, fishing at wharfs, and sand mining directly impacts children’s education. “Addressing this social problem requires collaboration across all sectors of society.

It’s not just a government issue; everyone has a role to play in protecting our children’s rights and breaking the cycle of poverty,” said Mr Sorie.

He shared that children often drop out to focus on earning money from stone mining, especially since they frequently go to school hungry.

Sorie emphasized that poverty is a core driver of child labor. When discussing the dangers, he said that many parents responded that their children’s participation is out of economic necessity these works are their primary survival strategy. He stressed that, despite existing laws and policies, enforcement remains weak.

Advocates argue that this persistent issue underscores the urgent need for stronger enforcement of child labor laws, better access to education, and socioeconomic support for vulnerable families. Protecting children from exploitative labor is essential to safeguarding their rights, ensuring their education, and ultimately, breaking the cycle of poverty.This investigation was supported by BBC Media Action and funded by Deutsche

Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), co-funded by the European Union (EU).